northern part of Rancho San Antonio 3

northern part of Rancho San Antonio 3

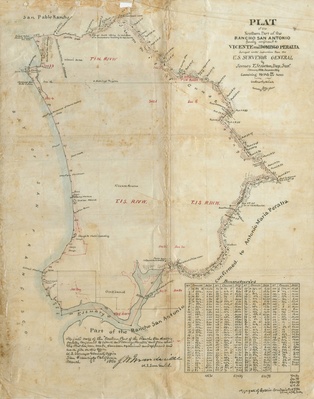

Rancho San Antonio was a 44,800 acre land grant made to Luís María Peralta (1759-1851) by the Spanish Crown in recognition of his forty years of military service. Peralta requested the land via a desiño ('design'), which included a hand-drawn map showing the area he wanted. It stretched from what is now San Leandro to Albany. It was granted by the last Spanish governor, Don Pablo Vicente de Solá on August 3rd, 1820. 2

Although he never lived there himself, Peralta's four sons, Hermenegildo Ignacio Peralta (East Oakland+San Leandro), José Domingo Peralta (Berkeley+Albany), Antonio Maria Peralta (east of Lake Merritt), and Jose Vicente Peralta (west of Lake Merritt including Temescal) built homes, took care of the family's livestock, and raised their families on the rancho.

Before the arrival of the Spanish, the land had been inhabited for approximately 15,000 years by native peoples, although by 1806 most of them had been removed to settlements called rancherías or died from disease.

Peralta was required to take possession of the land within a year, so in 1820 a crude log and mud structure was built to house the vaqueros (cowboys) who managed the cattle. In 1821, Antonio Maria Peralta built the first adobe on the site. Around 1828, Antonio brought his first wife to live on the rancho. A larger adobe was built about 1840. The Italianate Victorian house (which still stands in Peralta Hacienda Historical Park) where Antonio lived with his family was built in 1870.

The four Peralta brothers eventually had more than 8,000 cattle and 2,000 horses on their land. The cattle were raised for their hides and tallow, not for meat. The cattle were processed near the foot of 14th Avenue (where ironically, a Burger King now stands). The Peraltas built an embarcadero (wharf) nearby to aid in trading.

Spanish Colonization

The Peralta family was part of the group of settlers that arrived in Alta California in 1776 on the famous de Anza expedition. Seventeen-year-old Luis Maria Peralta accompanied his father, mother and three siblings. This group of settlers subsequently helped found the San Francisco Presidio, Mission Santa Clara, and the pueblo of San Jose.

In 1820, Rancho San Antonio was given to Luís Peralta with the requirement that he establish a permanent dwelling on the property within one year. His third son Antonio Maria Peralta (1801-1879) built the first adobe on the site in 1821. Sometime around 1828, Antonio brought his first wife, Maria Dolores Galindo to live on the rancho and the other three sons of Luís María Peralta soon followed. Eventually, Vicente, Domingo and Ignacio Peralta all built their own homes in various parts of the rancho in order to better manage the large grant. José Domingo Peralta (1795-1865), who had his own rancho in present-day Santa Clara-San Mateo counties, was convinced to move to Rancho San Antonio in the 1830s and eventually built an adobe in 1841 in the northernmost part of the rancho in what is now the city of Berkeley. The oldest son, Hermenegildo Ignacio (1791-1874), after retiring as alcalde in San José, came to the rancho in 1835 and established a residence in the southernmost area in present-day northern San Leandro. The youngest son, José Vicente (1812-1871), lived with his brother Antonio until he married and built his own adobe in 1836 in what is now the northern Temescal district of Oakland.

With their wives, families, landless Mexican laborers, and surrounding native peoples, the Peralta sons established the first Spanish-speaking communities in the East Bay. The Peralta Hacienda became the social and commercial center of this vast rancho. The Peraltas eventually had over 8,000 head of cattle and 2,000 horses grazing on the rancho, and built a wharf on the bay near the hacienda headquarters in order to trade the hides and tallow produced by their cattle. Foreign trade had developed as a result of the takeover of Alta California by Mexico in 1822.

As the rancho prospered, the Peralta brothers built newer and bigger houses. On the site of Peralta Hacienda Historical Park, Antonio built a larger adobe in 1840. Eventually, this site contained two adobes, and some twenty guest houses, and became an established stop for travelers along the Eastern branch of the El Camino Real. Annual rodeos and cattle round-ups, horse racing, games, and fandangos-part of week-long celebrations-often took place here. The sons and daughters of the first Spanish and Mexican settlers who were born in California became know as Californios and their heyday is called the pastoral era of California history. Native peoples whose ancestors had occupied California for thousands of years worked and lived on the rancho and made its economic success possible.

In 1842, apparently believing it was time to settle his estate, eighty-three-year-old Luís María Peralta journeyed to the rancho in order to divide the rancho land among his four sons. Luís had already given cattle to his three married daughters and planned to leave his San José adobe and land to his two unmarried daughters, who lived with him. Antonio received 16,067 acres of land from 68th Avenue to present-day Lake Merritt and up the eastern side of Lake Merritt to Indian Gulch, now known as Trestle Glen. Antonio's portion also included the peninsula of Alameda. Ignacio received approximately 9,416 acres from southeastern San Leandro Creek to approximately 68th Avenue in Oakland. Vicente received the acreage that included the entire original town of Oakland, from Lake Merritt to the present Temescal district. Domingo received all of what is present-day Albany and Berkeley and a small portion of northern Oakland. The acreage of each portion is only known because of the patents later received by the brothers from the US government. Both Ignacio and Antonio received separate patents for their portions, but Vicente and Domingo applied for a joint patent that totaled 19,143 acres.

According to historian J.N. Bowman, the Peralta family built a total of 16 houses over a fifty-year period on Rancho San Antonio. There were eleven adobes, three frame houses, one brick house, and one built of 'logs and dirt' (the very first structure built). Only two of these sixteen houses are still standing: Ignacio Peralta's brick house built in 1860, which is part of the house now known as the Alta Mira Club in San Leandro, and the 1870 Victorian frame house built by Antonio which is now the focal point of Peralta Hacienda Historical Park, in the Fruitvale district of East Oakland. All of the other structures were either lost as a result of the 1868 earthquake, burned, or torn down for new development after being sold by descendants of the four brothers.

The Gold Rush and Statehood

The American annexation of California and the Gold Rush of 1849 had a tremendous impact on the lives of the Peralta family and other Californios. At first, the Americans guaranteed the Californios the right to their property and promised to recognize all land grants legitimately made by the Spanish and Mexican governments. Early American settlers often acted ethically and purchased or leased land from the Mexican government or the rancheros. The ranchos thrived through the early years of the Gold Rush because the price of cattle skyrocketed as a direct result of market demand. Later, as access to gold diminished in the Sierra foothills, two hundred miles east of Rancho San Antonio, disillusioned miners returned to the coast. They were part of a major increase in the state's population that also included Chinese laborers, European immigrants, and Yankees migrating to build new lives in the West. Some of these early settlers began squatting on rancho land. Rancho San Antonio was especially desirable because of its proximity to San Francisco, its fertile land, and its spectacular redwood groves.

Another turning point for the Peralta family occurred in 1851, when family patriarch, Luís María Peralta died, his estate valued at $1,383,500. This enormous figure probably represents the increase in property values that resulted from the development caused by the Gold Rush. Luis had told his sons not to go to the gold mines, stating, 'The land is our gold.' Luis may have been right, but the land was not going to be easy for the Peralta heirs to keep.

Although the United States government promised all rights of citizenship and property ownership to the Californios through the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo signed at the end of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the American government found other ways to legally cause the Californios to eventually lose their dominant place in California society. The 1851 U.S. Federal Land Act contributed to the fall of the rancho era, since it required the Californios to prove their land titles in court. The resulting litigation lasted years. In the interim, squatters continued to overrun Rancho San Antonio, stealing and killing cattle and even subdividing and selling land belonging to the Peraltas. Although the United States Supreme Court confirmed the Peralta title in 1856, the Peralta family had their own internal title dispute to resolve. The Peralta sisters, possibly spurred on by their husbands and American attorneys, apparently felt cheated out of the family land, and contested their brothers' claim to the Rancho San Antonio land grant. The court case, known as the 'Sisters Title case' was eventually resolved in the brothers' favor by the California Supreme Court in 1859.

When the star of the Spanish-speaking settlers fell, that of the Native Californians was nearly extinguished. The US did not view Native Californians as essential to their economy as the rancheros had during the Mexican era, nor as souls to be saved, as many of the mission priests had, but as a scourge to be eliminated. Many of the new entrepreneurs now saw the Spanish-speaking population, including former rancheros, as the next cheap labor force.

By 1860, the brothers' land holdings had been substantially reduced, partly to pay for the previous decade's litigation and to cover newly imposed property taxes. When Antonio's 1840 adobe was made uninhabitable by the 1868 Hayward Fault earthquake, Antonio and his family moved back into the 1821 adobe. In 1870, after removing the debris of the 1840 adobe, the guesthouses, and the hacienda wall, Antonio built the Italianate Victorian two-story frame house. By this time, the rancho era was near a close and the values, culture, and customs of the newcomers had replaced those of the Californios. Evidence of this transition, including the transfer of wealth, is reflected in the architecture of the 1870 wooden frame house. It stands in sharp contrast to the adobe residences it replaced; yet also bears little connection to the ornate Victorian homes built at the same time by prosperous Bay Area residents of American or European descent.

In 1872, the combined property of the sons of Luís María Peralta was assessed at approximately $200,000, a substantial decrease in the family's wealth. Antonio, (the last of Luís María Peralta's sons), died in 1879. At the time of his death, Antonio owned his own home and had 23 acres left of the original 16,067 acres he had received from his father. The property was valued at $15,000 when the estate was probated two years later. Not a huge estate by the standards of the time, but still a substantial home in his neighborhood. Antonio had sixteen heirs, but the house and land were deeded to Francisco Galindo (husband of Antonio's daughter Inez) in trust in payment of a $5,000 debt.

Like many families, Antonio María Peralta's children fought over the handling of the estate and there are surviving letters that discuss financial problems experienced by the adult children, and the need to sell off land for money. In the end, the 1870 house and the last eighteen acres of Antonio's share of the land grant was sold by his daughter Inez Galindo in 1897 to a developer named Henry Z. Jones. The house was moved across the street and a housing development called the Galindo tract resulted. The last remnants of the 1821 adobe were also removed from the site at this time and some of the bricks were used to build the Dimond Lodge in Dimond Park, Oakland. Fifty years after the American annexation, the last of the headquarters of Rancho San Antonio was gone.

Peralta Hacienda Historical Park represents an historic landscape that witnessed the rise and fall of the Spanish-speaking, land-owning Peralta family, and the fate of the landless Mexicans and Native Peoples with whom their fate was linked. The history of its creek, adobe rancho area and 1870 Peralta house spans the nineteenth century, during which time the land was transformed in turn by settlers from Spain, Mexico and the United States. 1

Links and References

- Peralta Family History on Peralta Hacienda website

- Rancho San Antonio on Wikipedia

- copl_005_item01_page001 Oakland History Center, Oakland Public Library