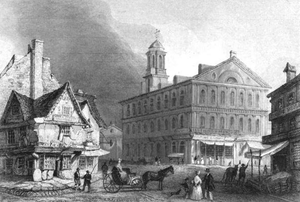

Located near Government Center in Boston, Massachusetts, Faneuil Hall is a marketplace and assembly hall. It was constructed from 1740 to 1742, before opening its doors in 1743. Built by John Smilbert, in the style of an English market, the hall contained an upstairs assembly room and ground level market house.

Pronounced “funnel” during the American Colonial Era, the hall was named after Peter Faneuil, a wealthy American colonial merchant, who donated the building to the city of Boston. A slave trader and philanthropist, who lived from 1700-1743, his hall served as a backdrop for slave auctioning blocks.

In addition to serving as a hub of commerce, primarily for food and goods, the hall became a rallying point for American colonists, who encouraged independence from Great Britain. Speeches from individuals, such as George Washington, Timothy Fuller, Edward Everett, Daniel Webster, Charles Francis Adams Sr. and Samuel Adams, were given there.

In 1742, Deacon Shem Drowne built a copper and gold leaf weathervane, which was installed atop the hall. Modeled after the London Royal Exchange’s weathervane, the design mimics that of a grasshopper. It was stolen, and subsequently returned in 1974.

In 1762, the city had to reconstruct the building, after it was burned to the ground the year before. Financed in part by a state-authorized lottery, it was re-opened on March 14, 1763. James Otis Jr. gave an address for the occasion, regarding the hall as an important site for the cause of liberty. Into the late 1700’s, the hall continued to serve a variety of purposes, at one point being used for theatre, during the Red Coat occupation. In addition, it was used as the rallying spot for Samuel Adams and the colonists, during their war for independence.

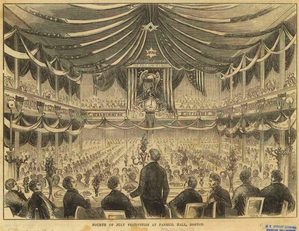

On July 4, 1777, George Washington celebrated the country’s first Independence Day at Faneuil Hall.

1800's Faneuil Market. Image in the public domain.

1800's Faneuil Market. Image in the public domain.

Beginning in the 1800’s, the greater marketplace surrounding Faneuil Hall expanded, to include Quincy Market, North Market and South Market. With its cobblestone grounds, granite walls, and Grecian-Doric architecture, Quincy Market has become a distinct hub of commerce, continuing to flourish in the 21st century.

1806 saw the addition of a third floor, with an expansion led by Charles Bulfinch. These changes lasted through most of the 1800’s, until it was rebuilt in 1898-1899, utilizing newer, safer materials.

It later became a prime location in Boston’s abolitionist movement. Escaped slave and abolitionist Frederick Douglass spoke at the hall on May 31st, 1849, some 106 years after Peter Faneuil’s death. In what is now known as Douglass’ Address to the New England Convention, the speech was met mainly with applause, and some hissing.

In August of 1890, one of the first black U.S. legislators, Julius Caesar Chappelle, gave a speech in support of the Federal Elections bill, which aimed to give blacks the right to vote. Printed on The New York Age newspaper’s front-page, on August 9, 1890, the title “At the Cradle of Liberty,” was given to the speech.

Faneuil Hall was named a National Historic Landmark on October 9, 1960. It now resides in the National Register. Restoration and alteration continued from the 1970’s through 1992. In 1994, the Boston Landmarks Commission dubbed it a local “Boston Landmark.”

In 2012, the bottom two floors were re-renovated, this time by Eastern General Contractors, Inc. These changes came only five years after the repairing of the bell in 2007. According to The Boston Globe, at the time of its repair, the last known ringing of the bell via its clapper had come in 1945 at the end of World War II.

Faneuil Hall, 2017. Image in the public domain.

Faneuil Hall, 2017. Image in the public domain.

Faneuil Hall regularly serves as the backdrop for street performers. These street performances first began in the 1970’s, as a way to entertain construction workers. To this day, visitors will often find large crowds gathered out front of the hall, watching everything from acrobats and magicians, to fire-eaters and comedians.

In the late 2010’s, activists set their sights on Faneuil Hall, advocating for the changing of its name. Protests and boycotts have taken issue with the tribute the hall pays to a known slave trader. In 2020, after the killing of George Floyd sparked national outrage, activists once again turned to protest, pushing for the renaming of the hall, as well as the removal of various statues and symbols.

Importance to the local community

The building of Faneuil Hall was highly controversial amongst those in the local community. The Boston Town Meeting vote passed, with 367 votes for it, and 360 votes against it. Since then, however, the hall has served an important purpose. Built primarily as a marketplace and auditorium, the hall provided a gathering place for citizens to socialize and attend events.

July 4th, 1853. Image in the public domain.

July 4th, 1853. Image in the public domain.

While it is still historically important in the twenty first century, the hall served as a location for the distribution of food, goods and ideas. It was a place for the local community to protest, discuss political issues, and social issues.

Nowadays, the hall’s historical significance, and status as a landmark, help the city attract business via tourism. With grounds once walked upon by the likes of George Washington and Samuel Adams, people from around the globe flock to Boston regularly.

After the Boston Marathon bombings on April 15, 2013, apparel and gifts with the term “Boston Strong,” have become a mainstay in the marketplace. The local community, by and large, shows great pride in their strength and resilience.

Faneuil Hall is important to many for what it represents. It is the very building where Bostonians protested the taxes levied upon them by the crown. It is the building, donated by a slave trader, that became a fixture of the abolitionist movement to end slavery. It is where John F. Kennedy spoke in 1960, stating his hopes for the future of the country. It is a beacon of freedom, a landmark of hope, and as it was dubbed following James Otis, Jr.’s 1763 speech, “The Cradle of Liberty.”

Works Cited:

(1) National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/bost/learn/historyculture/fh.htm

(2) Faneuil Hall Marketplace, https://faneuilhallmarketplace.com

(3) NPR, “Faneuil Hall’s Ties to Slavery Sparks Debate in Boston,” https://www.npr.org/2018/08/16/639149671/faneuil-hall-s-ties-to-slavery-sparks-debate-in-boston

(4) Boston.gov, https://www.boston.gov/news/black-history-boston-frederick-douglass-speaks-faneuil-hall

(5) Explore Boston, https://explorebostonhistory.org/items/show/23

(6) Boston.com Archive, http://archive.boston.com/news/local/articles/2007/05/04/it_tolls_for_the_city/

(7) The Guardian, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/jul/31/faneuil-hall-boston-boycott-slavery

(8) Boston.com, https://www.boston.com/news/local-news/2020/06/23/hunger-strike-renaming-faneuil-hall

(9) “Quintessential Boston Attractions Faneuil Hall Marketplace,” https://www.reverehotel.com/blog/quintessential-boston-attractions-faneuil-hall-marketplace

(10) CBS Boston, https://boston.cbslocal.com/top-lists/5-things-you-didnt-know-about-faneuil-hall/

(11) Trolley Tours, https://www.trolleytours.com/boston/faneuil-hall

(12) The Liberator, http://theliberatorfiles.com/great-meeting-at-faneuil-hall/

(13) Celebrate Boston, http://www.celebrateboston.com/sites/faneuil-hall.htm

(14) Celebrate Boston, http://www.celebrateboston.com/sites/faneuil-hall-grasshopper.htm