Background

The first offshore drilling operation was located in Summerland, California.

The first offshore drilling operation was located in Summerland, California.

Offshore oil drilling began in the Santa Barbara area in 1896 with the world’s first offshore drilling in Summerland, California, occurring on piers in the Summerland Oil Field. As technology for offshore drilling improved, the Santa Barbara area saw the development of what is now Rincon Island, a manmade drilling island. Oil company geologists later discovered the likelihood of oil reservoirs under the sea floor in the Santa Barbara Channel.

After the passage of the federal Submerged Lands Act in 1953, which granted tidelands within 3 nautical miles to states, the state of California began granting leases to the oil fields in the newly-recognized state waters of the Santa Barbara Channel in 1957. The first offshore oil platform to be erected was platform Hazel, in 1957, followed by the adjacent Hilda in 1960. Platform Holly was built by ARCO in 1966 just two miles from the Goleta coast above 211 feet of water. It is a notable obstruction to the view of the Pacific Ocean and Channel Islands from the University California Santa Barbara campus. Development of oil drilling in federal waters outside of the 3 mile nautical range began soonafter.

Partial map of oil platforms in Santa Barbara Channel. Note Platform Holly in upper left, and Platform A in center-right

Partial map of oil platforms in Santa Barbara Channel. Note Platform Holly in upper left, and Platform A in center-right

Leasing of federal waters for oil drilling began in 1966 and the first platform, Platform Hogan, became operational in 1967. Union Oil, Gulf Oil, Texaco, and Mobil formed a partnership to purchase the lease of the Dos Cuadras Offshore Oil Field on February 6, 1968. Their first rig, Platform A, was erected on September 14, 1968. It was built 5.8 miles from the shore of Summerland above 188 feet of water.

Platform A would operate for just over 3 months before causing a massive oil spill that now ranks third in size in the history of oil spills in the United States.

1969 Santa Barbara Oil Spill

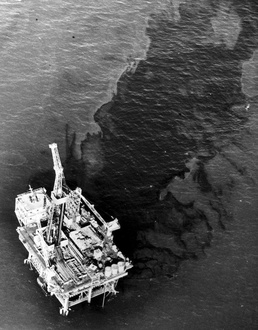

Oil leaks from beneath Platform A

Oil leaks from beneath Platform A

On January 28, 1969, after reaching a depth of 3,497 feet below the seafloor, riggers penetrated a high pressure oil zone. A decision was made to retrieve the drill to replace the drill bit. However, as the drill was extracted, the difference in pressure as the drill was removed was inadequately compensated for by the pumping of mud back down the well. The pressure increase caused the oil from the high pressure zone below the seafloor to flow up the well and erupt into the air. Workers futilely attempted to place a cap on the pipe against over 1000 pounds per square inch of pressure, but were unable to contain the flow of oil. Workers then dropped the half-mile drill pipe into the hole and rammed the top of the well shut with two giant steel blocks, which ended the flow of oil to the surface.

A cross section illustration depicting the drilling pattern of Platform A.

A cross section illustration depicting the drilling pattern of Platform A.

However, without a point of release for the oil, pressure within the well continued to increase. Under normal drilling procedures, the well might have held together under a certain amount of pressure, but it was soon realized that the well-reinforcing casing was inadequate to hold the well together under the immense pressure. Prior to the well blowout, the United States Geological Survey granted Union Oil a waiver that allowed them to place less casing in the well. Where 300 feet of primary casing and 870 fees of secondary casing are normally required to be placed in a well under federal regulations, Union Oil had used only 239 fees of primary casing. The well walls below this had no reinforcement. As a result, the pressure in the well forced oil through the walls of the well, creating five cracks in the sea floor through which oil began to seep into the ocean at a rate of 1000 gallons an hour.

Spread

The oil slick reached land on February 5, 1969. Santa Barbara residents soon found their beaches blackened and smelling of crude oil, and witnessed the horror of dead and dying birds covered in muck. Oil was as thick as 8 inches on some beaches, and several inches deep on the surface of the Santa Barbara Harbor waters, blackening most of the 800 boats there. Santa Barbara resident Kim Sturmer recounts his encounter with the oiled beach in his surf journal:

Photo of a surfer covered in oil from the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill.

Photo of a surfer covered in oil from the 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill.

“Went out at Miramar Point in the morning, but I was totally saddened by the way the beach looked. Oil everywhere. When I paddled out, I could feel that some oil had settled and covered the rocks in the intertidal zone. And the top of my board got so thoroughly coated with oil that wax had absolutely no effect. My board was so slippery I couldn’t really surf well, so I came in. Very few people went surfing this weekend.”

-Kim Sturmer, Santa Barbara Resident

The seepage would continue for 11 days, spewing 3 million gallons of oil into the ocean in the Santa Barbara Channel, creating an oil slick that reached a length of 35 miles, and tarring beaches from Rincon point to Goleta and the beaches of the Channel Islands. The seeping cracks in the ocean floor were eventually sealed with chemical mud and cement on February 8, 1969, though new seepages occured intermittently in the area until at least 1970.

Cleanup

Cleanup after the main spill lasted for 45 days. Initial cleanup efforts were overseen by United States Coast Guard and led by Union Oil. However, the federal government took control of cleanup supervision on February 4, 1969, noted to be an unprecedented move at the time. Early efforts by Union Oil to control the spilled oil included the deployment of three crop dusting planes to drop a chemical dispersant over the oil slick, and boats pulling large booms to skim the oil from the surface of the ocean and dumping it onto barges. In the Santa Barbara harbor and on beaches, oil workers and clean up crews used hay to soak up oil. Oiled sand and hay was then bulldozed into large piles and hauled away by dumptrucks. Over the course of the cleanup effort, over 5,200 dumptruck loads of polluted debris was hauled to landfills.

Aftermath

Environmental Effects

The environmental impact of the oil spill was severe. Tides washed the corpses of dead seals and dolphins, some with oil-clogged blowholes, onto the blackened beaches. Barnacles faced up to a 90 percent mortality rate in some areas, and limpets and mussels were cooked in steam cleanings of the oiled rocks they were attached to as part of the cleanup effort. Lobster and crab fishermen found their catches alive, but coated with oil. Migrating gray whales avoided their normal route through the Santa Barbara Channel as they travelled south. Initial reports suggested that few mammals had died as a result of the spill, however, a Life magazine story featuring reports and photographs from San Miguel Island, the westernmost island lining the Santa Barbara Channel, counted over 100 dead sea lions and elephant seals-- mostly pups.

The environmental impact of the oil spill was severe. Tides washed the corpses of dead seals and dolphins, some with oil-clogged blowholes, onto the blackened beaches. Barnacles faced up to a 90 percent mortality rate in some areas, and limpets and mussels were cooked in steam cleanings of the oiled rocks they were attached to as part of the cleanup effort. Lobster and crab fishermen found their catches alive, but coated with oil. Migrating gray whales avoided their normal route through the Santa Barbara Channel as they travelled south. Initial reports suggested that few mammals had died as a result of the spill, however, a Life magazine story featuring reports and photographs from San Miguel Island, the westernmost island lining the Santa Barbara Channel, counted over 100 dead sea lions and elephant seals-- mostly pups.

A large number of birds, including muirs, grebes, gulls, and pelicans, were affected by the spill. Effort was made to save birds that had become coated with oil. Volunteers scoured beaches to rescue screaming birds that had become stuck in tar and deliver them to treatment centers. Oiled birds were delivered to the Ventura Humane Society, Santa Barbara Zoo, or Childs Estate bird center. At these centers they were treated with Polycomplex A-11 for oil removal, medicated, and placed under heat lamps. The survival rate was less than 30 percent for birds that were treated. At least 3,686 ocean feeding birds were estimated to have died as a result of the oil spill.

Cultural Impact

Nation-wide media coverage of the spill in press, radio and television spurred immediate public response. Images of dead and dying birds were seen across the country and are credited with arousing environmental concern among the public. In the Santa Barbara area, spontaneous civilian volunteer efforts to clean the spill began as soon as oil washed onto the beach. This included an organized effort to save some of the oiled birds.

“The Child’s Estate Zoo asked for volunteers to help collect injured seabirds and bring them into the zoo, so I volunteered. They said carry pads of butter and try to get them to swallow some butter to help emulsify the oil in their throats. I had good gloves, so I went with a big container and walked from Sharks Cove down to Loon Point and collected probably about 50 birds over a few day period and took them into the zoo.“

-- Kim Sturmer, Santa Barbara Resident

“Reports and images emphasized a sense of tragic, heartbreaking helplessness. Volunteers watched, the Los Angeles Times reported, as cormorants ‘tried vainly to clean one another off with their beaks,’ and then died from ingested oil.”

-- Kathryn Morse, for the Journal of American History

An ad pleading for volunteers to help save birds appeared in the UCSB campus newspaper, El Gaucho, on February 7, 1969.

An ad pleading for volunteers to help save birds appeared in the UCSB campus newspaper, El Gaucho, on February 7, 1969.

An ad calling for an on-campus rally at UCSB from the April 9, 1969 issue of El Gaucho.

An ad calling for an on-campus rally at UCSB from the April 9, 1969 issue of El Gaucho.

A poem from the April 29, 1969 issue of UCSB's campus newspaper, El Gaucho.

A poem from the April 29, 1969 issue of UCSB's campus newspaper, El Gaucho.

Concern about the oil spill among UCSB students, faculty, and community was apparent across campus. Students wrote the school newspaper calling for awareness and action. As one student states in his letter to the editor, “Americans need a disaster to wake them up to situations that have been worsening for years”, while another letter demanded “Let the Department of the Interior permanently seal off the black vomiting wells in the Santa Barbara Channel”. The Joint Isla Vista Effort (JIVE) organization sponsored a contest to seek more effective ways to clean oil from beaches. A student organized rally was held on campus. Concern about the spill even appeared in student poetry.

In the larger Santa Barbara community, people protested the continuation of oil drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel, rallying against United States President Nixon, Union Oil president Fred L. Hartley (who would refer to picketers as “wild animals and monsters”) occurred, as did tense city council meetings packed with citizens and students. One meeting became so contentious that the Mayor and city council members walked out. A rally organized by the newly formed environmental group Get Oil Out (GOO) near Santa Barbara Harbor’s Stern’s Wharf on April 6, 1969 inflamed protesters so much that acting Mayor Vernon Firestone spurred them to storm the pier where they drove away two oil supply trucks in a massive sit-in demonstration.

A January 9, 1970 sit-in protest on Stearn's Wharf in the Santa Barbara Harbor.

A January 9, 1970 sit-in protest on Stearn's Wharf in the Santa Barbara Harbor.

Other local government officials were active in the issue of oil drilling in Santa Barbara, though sometimes sitting on opposing sides of the issue. Santa Barbara city councilman Klaus Kemp was once accused in a public meeting of being “the biggest oiler around here” due to his oil interest associations. Santa Barbara County Supervisor George Clyde was an outspoken opponent of oil presence, quoted as saying “everyone in the interior department was hell bent to get oil leasing in this area as early as 1966. We need help and protection”, and “When they (the oil companies) came before us a few years back they assured us a thing like this could never happen”. In the end, neither the city nor the county of Santa Barbara would stop oil drilling in the Santa Barbara Channel.

Legislation

Aerial image of the oil spill in Santa Barbara Harbor.

Aerial image of the oil spill in Santa Barbara Harbor.

Federal legislation was enacted in the years after the oil spill, which saw the formation of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, the National Environmental Policy Act, and the Clean Water Act. Within the state of California new legislation created the California Coastal Commission, and enacted the California Environmental Quality Act. Though not solely responsible for these legislations, the Santa Barbara oil spill was the most visible event that led to the new environmental laws. It has been noted that the period after the oil spill saw more environmental legislation than any other time in U.S. History.

Economic Impact

Lawsuits were filed against Union Oil by both government and individual citizens in class-action suits with Union Oil eventually settling all suits for several millions of dollars. After federal policies were implemented following the oil spill, offshore oil platform operators were required, by law, to pay boundless amounts of cleanup fees as well as $35 million in penalty fees.

Contamination of the previously scenic Santa Barbara Harbor caused economic hardships for the local tourism and fishing industries.

Contamination of the previously scenic Santa Barbara Harbor caused economic hardships for the local tourism and fishing industries.

Nearby fisheries and mariculture resources felt the economic impact as well. Fishing operations in the area were temporarily suspended, causing substantial losses in profits. Physical contamination of the ocean affected fish stocks, and halted business activities as the oil polluted gear necessary for operations and hindered access to fishing sites. Local fishing was interrupted due to the contamination of the fish in the Santa Barbara Channel.

The oil spill also affected tourism, including recreational activities such as swimming, boating, and diving. The public was aware of the high level of contamination in Santa Barbara and avoided tourism in the area that was now nationally known as the site of an ecological disaster. Area businesses experienced an economic downturn as a consequence of the oil spill.

Present Day

Present day Santa Barbara Harbor.The Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 had lasting effects on communities around the world, and alerted the public to the dangers of offshore oil drilling and the devastating impacts it can have on the environment. The spill is considered to have spurred the modern environmental movement and resulted in the establishment of the Earth Day holiday.

Present day Santa Barbara Harbor.The Santa Barbara oil spill of 1969 had lasting effects on communities around the world, and alerted the public to the dangers of offshore oil drilling and the devastating impacts it can have on the environment. The spill is considered to have spurred the modern environmental movement and resulted in the establishment of the Earth Day holiday.

Senator Gaylord Nelson of Wisconsin founded the holiday in 1970, utilizing it to inform people about environmental issues, transform public attitudes, and emphasize the importance of protecting our planet. It is celebrated annually on April 22. By 2000, Earth Day began to focus on the importance of clean energy, and involved hundreds of millions of people in 184 countries and 5,000 environmental groups, according to the Earth Day Network (EDN).

Another positive outcome of the oil spill was the establishment of the Environmental Studies department at UCSB. Until the oil spill had occurred, little attention was brought to the importance of environmental protection. After experiencing the toxic effects of the oil spill in 1969, a group of faculty members called “The Friends of the Human Habitat”, met to discuss the idea of developing a program of environmental education at UCSB. By the fall of 1970, the Environmental Studies Program at UCSB was established and was one of the first of its kind in the United States. The first graduating Environmental Studies (ES) class was composed of just twelve students. Currently, there are more than 850 enrolled students with an ES major, as well as 6,500 UCSB ES alumni.

2015 Refugio Oil Spill

On May 19, 2015 an oil pipeline that runs along Highway 101 burst and caused the worst oil spill in the Santa Barbara area since the spill in 1969. The onshore pipeline is estimated to have leaked more than 120,000 gallons of oil on land with roughly 21,000 gallons going into the ocean. Although this spill was significantly smaller than the one in 1969, it still had damaging impacts to the environment and the community.

Causes

Oil approaching the show of Refugio State Beach.

Oil approaching the show of Refugio State Beach.

On May 19th, 2015 a low pressure alarm sounded from Plains All American Pipeline’s Line 901. The alarm sounded for more than 30 minutes before the line was shut down at 11:30am, however Plains did not confirm that the leak came from their line until 1:30pm, after the fire department reported the spill. The company then waited until 2:56pm to notify the National Response Corporation and Clean Seas, the clean-up company they use, that they needed assistance. By the time that the employee shut down Line 901 21,000 gallons of oil had leaked into the ocean, and the delay in notifying Clean Seas made the clean-up effort significantly more difficult.

Line 901 was built in 1987 and was the only pipeline in Santa Barbara County that did not have an automatic shut off valve. Plains routinely checked the pipeline every three years and repairs had been done in 2012, however the results from the 2015 check had not come in yet at the time of the spill. According to Channel 3 News, the rupture occurred at a spot on the pipeline that had been eroded so badly it was only 1/16 of an inch thick. Line 901 is considered an interstate pipeline and is required only to follow the federal regulations, not the much more stringent state regulations. The California fire marshal said that had the line been under state regulations it would have been considered “high risk” and been monitored much more closely.

Ecosystem Impact and Safety

There are roughly 800 species of plants and animals living in the kelp forests off the Santa Barbara Coast. When an oil spill happens, the ecosystem needs to be monitored to get an understanding of threats to both the ecosystem and humans that may come in contact with it. To analyze damages to the ecosystem, researchers had to select certain plants and animals from the ecosystem to look at tissue samples. These species included ones with potential exposure to the oil, ones of recreational or commercial importance, or ones that are particularly representative of the ecosystem health as a whole. If a species falls into any of these three categories, it has potential to be chosen. This included species like rockfish, surfperch, sand dabs, California spiny lobsters, warty sea cucumbers, crabs, sea urchins, abalone, and mussels. Once collected, the tissue samples were tested for oil contamination. This information could help researchers determine whether the ecosystem was above or below the Level of Concern. Above this level indicated it was too dangerous for human interaction, which was especially important for fisheries. They can’t be sending fish to restaurants that are contaminated and deemed unsafe for human consumption. Once the ecosystem drops below the Level of Concern, the area can be reopened to use. By June 29, 2015 it was decided the area was again safe in terms of human health risk.

An oil-covered Pelican on the beach at Refugio.

An oil-covered Pelican on the beach at Refugio.

This mainly focuses on human risk without taking into account the damage to animal species. It is estimated that more than 200 birds, 106 marine mammals, and an unknown amount of wildlife on the surf line were killed as a result of the spill. The birds get coated with the oil and are exposed to high concentrations of toxins from it. The oil also damages the waterproof layers on the bird’s wings by causing the feathers to stick together and clump up. This can leave areas on the bird exposed and makes them more sensitive to the cold water of the ocean.

The damage could have been a lot worse if it weren’t for previous oil spills in the area. The history of the spills resulted in certain legislation and protocols that caused an almost instantaneous and efficient response to cleaning up the spill once it was reported. This limited the damage significantly and saved countless animals’ lives.

Effects on the Community

The fishing industry took a huge hit, with a 26 mile by 7 mile area beige closed off immediately after the spill. 138 square miles of harvest grounds remained closed for over a month after the spill, spanning from Canada de Alegeria to Coal Oil Point, leading many local commercial fishermen to file claims against Plains. Fisheries in the affected area included lobster, crab, shrimp, halibut, urchin, squid, whelk, and sea cucumber, among others. After the spill occurred many companies saw hundreds of orders cancelled and thousands of dollars in revenues cancelled. A class action lawsuit brought by a group of local fishermen against Plains is still in litigation.

Map showing impact of spill on coastline.

Map showing impact of spill on coastline.

In addition to the fishing industry, many other ocean-based tourism businesses suffered as well. Multiple surf instructors were forced to cancel lessons, kayak, surf board, and paddle board rentals suffered, and countless fishing charters and sailing trips were cancelled. Restaurants in the area who rely on local seafood also suffered heavy losses. Hundreds of oil workers lost their jobs when ExxonMobil dramatically reduced their workforce. A second class action lawsuit was brought against Plains by a group of individuals claiming to have been hurt by the spill. The plaintiffs include oil workers, surf-camp owners, landowners, fuel suppliers, seafood distributors, and commercial fishermen.

Santa Barbara County is also suing Plains for damaging its “reputation as a world-class tourist destination.” The tourism industry did suffer major losses. The campgrounds at El Capitan State Beach and Refugio State Beach were forced to cancel reservation for over a month. At Refugio, those cancellations cost up to $8,000 per day, and that is not including the additional revenue lost from up to 2,000 individuals that flock to the beaches for day use.

Community Reaction

UCSB students call for the divestment of oil on UC campuses after the Refugio oil spill.

UCSB students call for the divestment of oil on UC campuses after the Refugio oil spill.

News of the oil spill led to shock, concern, and even anger within the coastal communities. A group of protesters marched through downtown Santa Barbara carrying a dummy pipeline nearly half a football field in length demanding transparency from the many government agencies involved in the response. A protest was held on the campus of UCSB to hold the chancellor accountable for UC investments in the oil industry. Abi Pastrana, an undergraduate involved in planning the protest described how she felt when she hear about the spill: “If I could choose one word to describe how I felt when I first heard of the spill I would say that I was devastated. Coming in as a brand new student at UCSB, I was amazed by the natural surroundings and beaches the university took pride in. So when I heard about the spill, I felt personally affected by it and saddened to see the environment polluted that way.”

Environmentalist groups such as the Environmental Defense Center, Community Environmental Council and Sierra Club California described themselves as being “saddened and disgusted” by the spill. They believe that there is no safe way to extract offshore oil and that the community needs to come together and “say no from now on.”

Families used to spending many summer days at the local beaches also expressed a deep sadness at the destruction caused by the spill. One local young adult recalled her reaction “I remember being in disbelief at first, and then sad and angry. I grew up going to Refugio and El Capitan, we camped at Refugio twice every summer. Seeing the pictures of the oil on the beach made me wonder how it could even be possible to clean it all up. It felt like the beach would never be the same.”

References

Potthoff, G. (2015, June 7). Local Fishing Industry, Businesses Still Struggling with Uncertainty of Oil Spill Impacts. Retrieved fromhttps://www.noozhawk.com/article/local_fishermen_businesses_struggling_with_oil_spill_impacts_20150607

Clarke, K. C. and Jeffrey J. Hemphill (2002)The Santa Barbabra Oil Spill, A Retrospective. Yearbook of the Association of Pacific Coast Geographers, Editor Darrick Danta, University of Hawai'i Press, vol. 64, pp. 157-162.

Meeks, K. (2015, December 1). Santa Barbara Fishermen File Spill Suit. Retrieved from http://www.fishermensnews.com/story/2015/12/01/features/santa-barbara-fishermen-file-spill-suit/362.html

Easton, Robert Olney (1972). Black tide: the Santa Barbara oil spill and its consequences. New York, New York: Delacorte Press.

Hamm, K. (2015, June 02). Fishing Industry Feeling the Pain After Refugio Oil Spill. Retrieved from http://www.independent.com/news/2015/jun/02/fishing-industry-feeling-pain-after-refugio-oil-sp/

Potthoff, G. (2015, July 16). Santa Barbara Suing Plains Pipeline Over Refugio Oil Spill. Retrieved from https://www.noozhawk.com/article/santa_barbara_to_file_suit_against_plains_all_american_pipeline_oil_spill

Kacik, A. (2015, August 12). Refugio oil spill cleanup costs near $100 million. Retrieved from https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2015/06/27/refugio-oil-spill-cleanup-costs-near-100-million/

Dubroff, H. (2016, May 27). Charges, lawsuits Plains' Refugio oil spill legacy. Retrieved from https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2016/05/27/charges-lawsuits-plains-refugio-oil-spill-legacy/

Kacik, A. (2016, August 26). Plaintiffs file for class certification in Refugio oil spill lawsuit. Retrieved from https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2016/08/25/plaintiffs-file-for-class-certification-in-refugio-oil-spill-lawsuit/

Bolton, T. (2015, May 28). Officials Extend Oil Spill Closures for Refugio, El Capitan State Parks. Retrieved from https://www.noozhawk.com/article/officials_extend_oil_spill_for_refugio_el_capitan_parks

Stout, M. (2015, May 25). Community Demands Transparency in Refugio Spill. Retrieved from http://www.independent.com/news/2015/may/25/community-demands-transparency-refugio-spill/

Magnoli, G. (2015, May 22). Santa Barbara Environmental Groups ‘Saddened and Disgusted’ by Refugio Oil Spill. Retrieved from https://www.noozhawk.com/article/santa_barbara_environmental_groups_refugio_oil_spill

Flores, O. (2016, August 30). Oil Spill Off Santa Barbara County Coastline. Retrieved from http://www.keyt.com/news/santa-barbara-s-county/oil-spill-off-santa-barbara-county-coastline/65431224

Russell, A. (2017, May 19). Refugio Oil Spill: What’s Happening Two Years Later. Retrieved fromhttp://www.ksby.com/story/35473707/refugio-oil-spill-two-year-anniversary-whats-happening-now

Lee, Quincy (2017, June 5). Platform Holly Decommissioned. Retrieved from https://thebottomline.as.ucsb.edu/2017/05/platform-holly-decommissioned

Mai-Duc, Christine (2015, May 20). The 1969 Santa Barbara oil spill that changed oil and gas exploration forever. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-santa-barbara-oil-spill-1969-20150520-htmlstory.html

Panzar, J. (2015, June 3). Ruptured Pipeline Was Corroded, Federal Regulators Say. Retrieved from http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-oil-spill-pipeline-20150603-story.html

(2016, May). Refugio Oil Spill Response Evaluation Report: Summary and Recommendations from the Office of Spill Prevention and Response. Retrieved from https://nrm.dfg.ca.gov/FileHandler.ashx?DocumentID=122847

(1992, February). Archives of the State Lands Commission: 1992 application for abandonment of Platform Hazel. Retrieved from http://archives.slc.ca.gov/Meeting_Summaries/1992_Documents/02-05-92/Items/020592C08.pdf

Websites

http://www.keyt.com/news/santa-barbara-s-county/oil-spill-off-santa-barbara-county-coastline/65431224

https://www.noozhawk.com/article/santa_barbara_environmental_groups_refugio_oil_spill

http://www.independent.com/news/2015/may/25/community-demands-transparency-refugio-spill/

https://www.noozhawk.com/article/officials_extend_oil_spill_for_refugio_el_capitan_parks

https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2016/08/25/plaintiffs-file-for-class-certification-in-refugio-oil-spill-lawsuit/

https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2016/05/27/charges-lawsuits-plains-refugio-oil-spill-legacy/

https://www.pacbiztimes.com/2015/06/27/refugio-oil-spill-cleanup-costs-near-100-million/

https://www.noozhawk.com/article/santa_barbara_to_file_suit_against_plains_all_american_pipeline_oil_spill

http://www.independent.com/news/2015/jun/02/fishing-industry-feeling-pain-after-refugio-oil-sp/

http://www.fishermensnews.com/story/2015/12/01/features/santa-barbara-fishermen-file-spill-suit/362.html

https://www.noozhawk.com/article/local_fishermen_businesses_struggling_with_oil_spill_impacts_20150607

http://www.ksby.com/story/35473707/refugio-oil-spill-two-year-anniversary-whats-happening-now

http://www.latimes.com/local/lanow/la-me-ln-oil-spill-pipeline-20150603-story.html